By Tobin Owl

Introduction:

In this timeline, compiled from various sources, the following salient points will be observed:

1) That the idea of contagion had a long history prior to the discovery of microorganisms by Leeuwehoek in 1676 and to Pasteur’s germ theory that began to take hold after the 1860s

2) That the “anticontagionists”, who gained sway in the first half of the 19th century—notably Chervin, MacLean, Magendie, Vichow, Pettenkoffer, Aubert Roche—were eminent and influential men of science who saw themselves as engaged in a battle with conservatism and long-held superstitions, one of whose main objectives was to bring an end to quarantines and military cordons that surrounded ‘infected’ towns. In this, they upheld human dignity and freedom of self-determination, as well as generally representing the interests of the bourgeoisie and merchant class. They were progressives and liberals; says Ackerknecht, “they were reformers, fighting for the freedom of the individual and commerce against the shackles of despotism and reaction.” Meanwhile the “leading contagionists (with the lone exception of the liberal professor Henle) were high ranking royal military or navy officers like Moreau de Jonnès, Kerandren, Audouard, Sir William Pym, Sir Gilbert Blane, or bureaucrats like Pariset, with the corresponding convictions.” [the Fauci’s and Drosten’s of the 19th century] (See Ackerknecht’s “Anticontagionism

between 1821 and 1867”, from which much of this part of the history will be drawn). According to

Ackerknecht, none of the ‘anticontagionists’ claimed that no disease was ever transmitted from human to human, but rather that certain prominent diseases claimed to be contagious were not—though it’s interesting to note that though smallpox was one of the afflictions that some anticontagionists believed to be truly contagious, Florence Nightingale believed otherwise (see quote from Notes on Nursing under 1860). The actions of the anticontagionists, far from being exclusively that of opposition to the contagionist establishment, were pragmatic and far-reaching: they were the primary proponents of much needed sanitary reforms, due to their belief that many illnesses, particularly the ‘quarantine diseases’, were not due to the purported human to human transmission or importation from abroad, but rather to the horrendous living conditions of 19th

century populations—particularly in industrialized cities that had few or no water closets, poor or inexistent sewer systems, crowded living conditions, poor lighting and ventilation, and lacked supplies of clean water for drinking and bathing and whose populations often lacked adequate nutrition (much akin to the conditions that still exist in certain places in developing countries, where the same illnesses that were prevalent in 19th century Europe and America, such as cholera, continue to persist). The anticontagionists were were therefore also the great leaders of the hygiene movement, though as Latour shows in The Pasteurization of France, that movement, which would continue well into the age that began to be dominated by Pasteurian germ theory in the late 19th and early 20th centuries, would be eventually transformed and narrowed by it, and at last identified with it.

3) That the dramatic decline in morbidity and mortality from nearly all of the great infirmities that plagued 18th and 19th century Europe and America can be directly attributed to sanitary reforms, principally impulsed the anticontagionists, during the 19th and early 20th centuries, and, conversely, is not attributable to vaccination, nor to the advent of antibiotics or other medical interventions. Antibiotics were not introduced until the first half of the 20th century. Meanwhile, as the graphic below demonstrates, vaccines for most of the major diseases of the 19th century were also inexistent until well into the 20th; with the primary exception of the smallpox vaccine (which this timeline also demonstrates to have been a failure).

4) That the final predominance of contagionism (as expressed in Pasteurian germ theory) can be attributed, at least in part, to the influence of French chemist Louis Pasteur and the German physician Robert Koch, each of whom were principal representatives of the interests of their respective governments. As Gradmann points out in Money and Microbes: Robert Koch, Tuberculin and the Foundation of the Institute for Infectious Diseases in Berlin in 1891, “Recently... historians have pointed to the fact that in contemporary writings and subsequent historiography there is an element of deliberate exaggeration of the importance, efficacy and conclusiveness of bacteriological science... Other historical research suggests the notion of germs as causal agents of disease should be seen as growing out of an intrinsic connection of political ideas of the imperialistic age with laboratory technology and procedures.”

5) That Pasteur was not the originator of his theory of germs, and that his conversion from being a believer and promoter of the idea of spontaneous generation was not effected until the fall of 1860, and thereupon the almost immediately jumped to new conclusions about airborne germs that were generally as unsubstantiated and incoherent as his previous beliefs about spontaneous generation. But owing to his self-exalting character, to deception, and to favor with certain important persons, including the Emperor, his theories became popularized. Meanwhile, the careful French physician, scientist, and professor Antoine Béchamp kept himself busy at work in the laboratory, and his discoveries were often ignored or perverted, and attributed to another.

6) That Béchamp’s diligent studies, both in laboratory experiments and in his studies of the natural world, led him, his close associate Professor Estor, and later his son Joseph—among other colleagues—to a comprehension of the processes of life, of disease, and of decomposition distinct from Virchow’s theory that the cell is the basic unit of all life, and distinct and more intricate than the germ theory as handed down to us by Pasteur and his followers—despite the fact that Béchamp, rather than Pasteur as it is claimed, was the first to demonstrate the role of living organisms in fermentation, and in the silkworm disease known as

pébrine. Integral to Bechámp and Estor’s deeper understanding were what Béchamp came to call

microzymas—visible only as granulations or scintillating specks under a microscope—which, through innumerable painstaking experiments, they concluded were the true units of life, able to transform or combine into more complex forms, passing through various mutations to form cells and bacteria, and affecting all the processes of metabolism and organic decomposition.

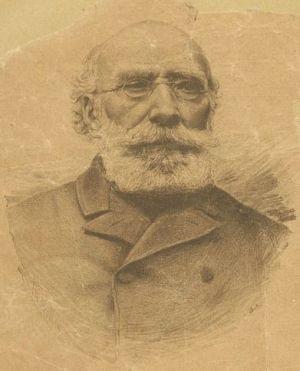

Antoine Bechámp

7) That Pasteur, who had been mediocre at chemistry in school—but who was sly and very effective at promoting himself in elite circles—repeatedly followed a pattern of first rejecting any of Béchamp’s assertions; then, when they became undeniable, adopting and perverting his ideas and claiming to be the first to have propounded them; and finally, when frustrated in his claim of priority, proceeding simply to use his influence to berate and dismiss Béchamp’s theories. “The world might have been spared the propagation and inoculation of disease matters (i.e. Pasteur’s vaccinations), had the profound theories of Béchamp been followed, instead of the cruder yet fashionable germ theory of disease, which appears to consist of distorted half-truths of Béchamp’s teaching.” (Hume, 1923). Indeed, we would be living in a different world.

Louis Pasteur

8) That the word ‘virus’ (Latin, “poison”) has carried with it various meanings and usages in science since the early investigations of 19th century bacteriologists and infectologists—in the 1800s, ‘virus’ appears to be used in biology to refer to any agent of disease, particularly in liquid form—before finally congealing into the meaning generally perceived today of an ‘infectious protein of genetic character’, following the unproven hypotheses of John F. Enders, concerning measles virus, in 1954.*

9) That subsequent to Enders winning the Nobel prize in 1954, all virologists have followed Enders’ methods for the ‘detection of a pathogenic virus’—methods which did not, and to this day do not, include true isolation of any so-called virus, and do not include control experiments, and remain therefore unscientific, and whose lack of proper scientific foundation was borne out in the recent measles virus court proceedings in Germany, in which, in 2016, examining the evidence including the testimonies of several expert witnesses, the unanimous judgement (3:0) of the Higher Regional Court of Stuttgart (later upheld by the German Federal Court of Justice) was that there is no conclusive proof of the existence of a measles virus in any of the primary so-called ‘scientific papers’ on the subject, including Enders’ original 1954 publication. As that publication’s acceptance represents the foundation of modern genetic virology, the assumptions about the nature and existence of all so-called pathogenic viruses are brought seriously into question.

* It should be noted that, even today, virology continues to evolve and the term ‘virus’ is now no longer used exclusively of an alleged ‘infectious’ or ‘pathogenic’ agent or protein. However, along with evolutionary biologist Stefan Lanka, I would submit, that the word ‘virus’ should no longer be used in any such sense, whether of so-called ‘pathogenic viruses’ or otherwise, due to long engrained connotations, misconceptions, and outright confusion surrounding the word. There are better alternative terms that more accurately describe the particles or phenomena under discussion.

Sources for this timeline

Though Dawn Lester and David Parker’s book, What Really Makes You Ill (2019), gave impetus to my final determination to compose a timeline of germ theory, that book did not provide me with the kind of clarity and documentation I desired; thus I have turned to other sources. Among the sources I have studied, I have found four works to be excellently well-researched and well-documented.

Two research papers:

Ackerknecht, “Anticontagionism between 1821 and 1867” (1948), and,

K. Codwell Carter, “Koch’s Postulates in Relation to the Work of Jacob Henle and Edwin Klebs” (1985)

And two books:

Ethel Douglas Hume, Béchamp or Pasteur: A Lost Chapter in the History of Biology (1923), and,

Suzanne Humphries and Roman Bystrianyk, Dissolving Illusions: Disease, Vaccines and the Forgotten History (2015).

I have also made use of R. B. Pearson’s, Pasteur: Plagarist, Impostor: The Germ Theory Exploded, originally published in 1942, though much of it’s material is based on Hume’s prior excellent work and I cite directly from Hume wherever possible. Hume derived her work largely from direct personal study of the records of the French Academy of Science.

Both Ethel Hume’s work, and that of Humphries and Bystrianyk, include numerous long quotes from primary sources of the period under discussion, and utilize footnotes on the same page to denote precisely where quotes were taken from. This method of documentation and annotation is, to me, laudable and lends much credibility to their work. In this timeline, I have attempted to do likewise wherever possible. Some may protest that the sources I have chosen do not reflect the orthodox history of medicine or biology. To that I will respond that it is not my intention to recapitulate orthodoxy. Rather it is the history that orthodoxy has neglected that I find both more interesting, and more compelling and meaningful. Finally, by way of presenting this timeline, I feel that the Ackerknecht‘s concluding remarks are worth reproducing here, and his final statement is as relevant today as it was in 1948:

“This strange story of anticontagionism between 1821 and 1867 – of a theory reaching its highest degree of scientific respectability just before its disappearance; of its opponent suffering its worst eclipse just before its triumph; of an eminently “progressive” and practically sometimes very effective movement based on a wrong scientific theory; of the “facts,” including a dozen major epidemics, and the social influences shaping this theory – offers so many possible conclusions that I feel at a loss to select one or the other, and would rather leave it to you to make your choice. I am convinced that whatever your conclusions, whether you primarily enjoy the progress in scientific method and knowledge made during the last hundred years, or whether you prefer to ponder those epidemiological problems, unsolved by both parties at the time and unsolved in our own day, all your conclusions will be right and good except for the one, so common in man, but so foreign to the spirit of history: that our not committing the same errors today might be due to an intellectual or moral superiority of ours.”

—“Anticontagionism between 1821 and 1867”. 191: 35–50. Erwin H. Ackerknecht, Zeitschrift Bulletin of the History of Medicine, Volume XXII, The Johns Hopkins Press, 1948.

Though many more things could be added to this timeline, in the desire to raise awareness on the issues presented I am making it available to the public it as it stands at present.

View timeline:

*Document may occasionally be updated and expanded